(The essay accompanying this CD was published in the run-up to an exhibition about Bo Cavefors, which was to be shown at Vita Kuben, part of Norrlandsoperan in Umeå, Sweden, between November 9 and December 4 2002. The exhibition had been put together by the Sons of God – Leif Elggren and Kent Tankred –, but was cancelled by Lars Sahlin, the local curator, on the eve of its opening. At the same time, my essay was removed from Norrlandsoperan’s website. Two flagrant acts of censorship that occurred on the anniversary of the Kristallnacht, November 9 1938. Leif Eriksson, January 31, 2003)

Leif Eriksson

ABOUT BO CAVEFORS

Signs in the sky

The light from a black bulb is also bright!

It just takes longer before you see it!

The analogy is with the eclipse.

Total solar eclipses occur with precise regularity. Everything stops, the birds fall silent, but our hearts beat on and suddenly it is evening. In the winter of 1979, darkness descended on Bo Cavefors’s publishing firm in Sandgatan, Lund, Sweden.

The corona ruined eyes. The smoked-glass eyepieces weren’t dark enough and left many people blind.

A serious disorder for those that would see. Thanks to the solar eclipse, we now know that space curves.

And others know more than they did.

Seen in such a compressed perspective, most things appear inessential, meaningless, even for a publisher.

But articles of the law, mucky bureaucracy and imbecility conspired to snuff out a unique publishing business.

This deplorable chapter of Swedish publishing history is still waiting to be properly chronicled. When will some postgraduate student lay claim to and explore this important area? It is a subject for several departments, eg literature, law, art history – not to mention all those students within the world of bookselling and libraries.

In contrast with the black, is the white more visible, or is it the other way around? You decide!

At the local level, ie Sweden, the eclipse became permanent. Human conventions and taboos played the major roles. Are we ourselves to blame for this state of affairs?

To be remembered for works done with a complete belief in the freedom of expression, regardless of creed, is reasonable. Plurality and free expression are things that everyone should strive for, since they mean freedom and the possibility to say that which can and must be formulated. Utopian thought.

On a primitive level, even the noblest aims can be ruined by narrow preferences and informal loyalties, not least liberal ones like the symbiosis between Lennart Eliasson, a public prosecutor, and Birgit Rodhe, then chair of the National Council for Cultural Affairs. He ordered humiliating searches to be made in Cavefors’s office and home, and kept him in custody for nine days, all according to the rules, but gained nothing of note in the end. Cavefors was only convicted of sloppy bookkeeping, and fined. And she nullified – with a stroke of her pen – Cavefors’s biggest publishing project, the Strindberg edition. Why?

Can these injustices be put right?

The exhibition in Vita Kuben at Norrlandsoperan, Umeå, Sweden, will present all 820 titles published by Bo Cavefors since 1959.

It began in 1959 with Brendan Behan’s play ”The Quare Fellow”, a tragicomedy, translated by Mario Grut. Behan’s ”The Hostage” was also published that year. Fateful titles, in retrospect. (Translator’s note: ”The Quare Fellow” was published as ”Den Dödsdömde”, or ”the condemned man”.)

As for the work to do with the publishing, Bo Cavefors ran a one-man show – though he did have four employees during the last four years.

During the two decades that his firm was in business, he achieved more than any other publishing house in Sweden in terms of selecting writers and works.

Frequently they were controversial writers, eg Ezra Pound or Ernst Jünger, but there was also other explosive political and philosophical writing by Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin and Mao, and texts such as ”Der RAF” [Rote Armé Fraktion].

It was probably that last title which clinched his judgement.

Not officially. Repressive tolerance had worked until then, but supporting terrorists? No, there are limits to the freedom of the press.

For Cavefors, freedom of expression still applies!

Allowing difficult and locally unknown writers to make their voices heard in Sweden was clearly too much.

Anyone who looks at the publisher’s last printed catalogue, with illustrations by Carsten Regild, a Danish-Swedish artist (1941-1992) – including, on the cover, his

congenial black light bulb (1978) which also illustrates my article, albeit turned upside down –, as well as a later supplement, is likely to marvel at its enormous variety and distinctiveness.

congenial black light bulb (1978) which also illustrates my article, albeit turned upside down –, as well as a later supplement, is likely to marvel at its enormous variety and distinctiveness.No other publisher in Sweden has achieved anything like it. The most important title is probably the one that never got published, but those that did get published highlight that important time now past, which – and that´s the scandal – clearly hasn’t become an accepted part of the historical flow.

Few contribute to radical knowledge and renewal.

The fear of new and different things is great.

Those who dare end get into the biggest trouble.

They are made to stand in the official cultural corner of shame, and punished for that ”widely accepted freedom of expression”.

Much energy is spent on cheating death; less on values, backbone, and on defending the particular.

It’s surprising, really.

Humanity is incredibly complacent and gullible that way.

Cavefors was not averse to any subject, any writer – as long as the manuscript was good. When I asked him why he published so many titles by Alexander Weiss, he replied laconically: ”I thought they were good”.

Anyone who wants to know more about what happened in the winter of 1979-1980 can read the exhibition’s facsimile of arts editor Nils Gunnar Nilsson’s articles in Sydsvenska Dagbladet, dated March 10 and April 13 1980.

Bo Cavefors himself has talked about what happened in an interview with Arne König and Lasse Winkler, published in Svensk Bokhandel, a booksellers’ trade journal (”Lundaförlagen, Cavefors ande vilar över Lund”, Svensk Bokhandel, 1997, no.2, pp. 13-26).

And for anyone who wants to know more about Bo Cavefors and about how it all started, I recommend two of his three books: ”Barnsliga memoarer” (”Childish memoirs”) from 1995 and ”Valpen som ung man” (”The whelp as a young man”) from 1996, both printed in Eslöv (the dreariest town in Sweden) and published by Förlaget Svarta Fanor. His other book, ”Helvetet” (”The Hell”), published by writer and editor Eric Fylkeson at Janus Förlag, 1985, is a collection of articles dealing with his Catholic faith and history.

Fylkeson wrote on the dust jacket: ”Cavefors’s contribution as a publisher during the 60s and 70s is legendary. Hundreds of unconventional and inconvenient books were injected into Swedish cultural life”.

Cavefors’s publishing efforts have not gone unnoticed over the years, however.

In his publisher’s archive are more than 20,000 press cuttings of reviews and articles, along with the unique correspondence he had with each of his many writers from around the world.

But when he offered this archive to Lund’s University Library, he was told that it might consider taking a selection.

That bloody well constitutes a breach of duty!

But, in 2004 Lund University, the Centre for languages and literature, acquired Cavefors’ Library and his Archives!

The complete list of publications shows that he published 13 central works by Peter Weiss. And 19 by his brother, Alexander Weiss! It also shows that Stig Claesson published his first book, ”Från nya världen”, with Bo Cavefors in 1961.

Nobel prizewinner Wole Soyinka was published by Cavefors in 1975, before he received the prize.

”Jungfrutro och Dubbelmoral” by Kristina Ahlmark-Michanek, 1962, became one of Cavefors’s top sellers, with five editions until 1963. It sparked the huge debate about sexual hypocrisy in Sweden.

But first something about the cultural context of the 60s, whose first half was marked by Swedish sin and the debate about free sexuality. There were loud and frequent calls for censorship.

Moderna Museet in Stockholm was inaugurated in 1958. A 1961 exhibition called Rörelse i konsten (Movement in Art) contained a work that was banned. It was by R. Müller, and entitled ”The Cyclist’s Widow”.

Its indecency consisted of a white dummy cock that bobbed up and down through a hole in the saddle when the pedals were turned. The great art debate ”Is everything art?” was raging at the time. Film censors were descending on Vilgot Sjöman’s film of Lars Görling’s ”491”. Per Oscarsson nearly showed his dick on Hylands hörna, the most popular family entertainment show on Swedish television in the 60s.

The Zinderman publishing house, in Gothenburg, released ”De erotiska minoriteterna”(”The Erotic Minorities”) by Lars Ullerstam in 1964, shedding light on necrophilia among other things. In 1965, Bengt Forsberg’s house in Malmö began publishing ”Kärleksböckerna” (”The Love Books”), edited by Bengt Anderberg, to great success. Anderberg himself got into trouble as early as 1948, with his first novel ”Kain”. When Pye Engström’s small bronze sculpture of a couple copulating was shown on TV in connection with Multikonst 1967, an art show, there was also an outcry – and the kindred, sorry, hundred couples were immediately sold.

The law against ”harming temperance and morality” reigned.

A number of Swedish artists were subjected to censorship. At Akademiska föreningen in Lund, Bengt Rooke conducted his Sex Evening in 1965: he painted a nude woman, ”who fainted”. Rooke swathed her in a Swedish flag, flung her onto his shoulder, and left. Several-page photo coverage followed in Se magazine, no.38. That provocation cost Rooke his teaching job. That same year (only earlier), Rooke had presented a performance entitled VROOM at Lunds konsthall. According to press reports of the event, it was ”openly pornographic!”.

Sture Johannesson was charged with the above-mentioned offence for having displayed, in the window of his Galleri Cannabis in Malmö, Lars Hillersberg’s scurrilous portrait of Sven Wedén, leader of the liberal People’s Party, trying to make his cock erect with the aid of a pair of pincers made at his tool factory in Eskilstuna. Hillersberg wanted to be prosecuted, see PUSS no.3 1968; Johannesson was, but was acquitted. PUSS, which published 24 issues between 1968 and 1974, was an incredibly important and provocative magazine, without parallel in Swedish periodical literature.

The May revolt of 1968 showed that the younger generation was politically aware. Flower Power and Hippies, ”make love not war” and the drug culture flourished, as did the Vietnam movement with its many demonstrations against America’s war in Vietnam – to which the police responded with brutality.

There were several scandals at Galleri Karlsson in Stockholm. The inaugural exhibition of Ture Sjölander’s pictures, ”Ni är fotograferad” (”You are being photographed”), showed a pair of naked ladies in the window, and TV and migration followed. At the same gallery, poet and artist Jarl Hammarberg showed his handwritten poster ”VÄGRA VAPEN VÄGRA VÄRNPLIKT” (”Refuse weapons refuse conscription”), in 1967. The prosecutor deemed it an incitement to rebellion, and Hammarberg was fined. When Carl Johan de Geer exhibited his three 1967 serigraphs, ”USA mördare” (”USA murderers”, with an American flag whose stars had been substituted for swastikas), ”Vägra vapen, vägra mörda, vägra mördas, svik fosterlandet, var onationell” (”Refuse weapons, refuse murder, refuse being murdered, betray your country, be un-national”), and ”Skända flaggan, Vägra vapen, Kuken” (”Desecrate the flag, Refuse weapons, The cock”), the editions were seized and destroyed after a guilty verdict in the court of appeal. See PUSS no.7, 1968.

Director Folke Edwards was fired from Lunds konsthall in 1969. He had mounted two important exhibitions, ”De otäcka” and ”Erotic Art”, but perhaps the main reason was that he had commissioned a poster for the ”Underground 1969” show, whose correct title was ”Revolution means revolutionary consciousness”, by Sture Johannesson. The ”hash propaganda” of the poster was the last straw for Konsthallen’s board, who stopped the show and forced Folke Edwards to resign.

In Uppsala in 1965, I was present when the police seized ”Man i bur, bekännelse av en homosexuell” (”Caged man, confession of a homosexual”), by Christoffer Palem (a pseudonym), because it had been deemed pornographic.

It was later allowed back on bookshelves after a court acquittal.

The law about harming temperance and morality was eventually scrapped.

Cavefors’s publishing comprises a wide range of titles. The following is a selection of authors, listed alphabetically.

Hans Arp, Fågel och Slips, translated by Benkt-Erik Hedin and Bengt Höglund, 1961.

Roland Barthes, four titles 1966-1975, Litteraturens nollpunkt, Kritiska essäer, Mytologier, S/Z.

Walter Benjamin, Bild och dialektik, 1969.

Hermann Broch, Vergilii död, 1969.

William Burroughs, Den nakna lunchen, translated by Peter Stewart, 1978.

Rolf Börjlind, Persona non grata, 1977.

Fredrik Böök, Kritiskt bokslut, 1976.

Pierre Cabanne, Dialog med Marcel Duchamp, translated by Jan Östergren, 1977.

Eight titles by Stig Claesson.

Three volumes by Maurice Cornforth, Marxismens filosofi, 1969.

Sture Dahlström, Gökmannen, 1975 and Den galopperande svensken, 1977.

Salvador Dali, Salvador Dalis hemliga liv, four editions 1961-1973.

Isidore Ducasse, Greve Lautrémont, Maldorors sånger, translated by Carl-Henning Wijkmark, illustrated by Ragnar von Holten, 1972.

Bob Dylan, sånger i urval, translated by Bruno K. Öijer and Eric Fylkeson, illustrated by Leif Elggren, 1975.

Umberto Eco, Den frånvarande strukturen, translated by Estrid Tenggren, 1971.

Leif Elggren, Nervsystem, 19 etchings. Accompanying text by Eric Fylkeson, 1976.

Michel Foucault, Vetandets arkeologi, translated by C. G. Bjurström, 1972.

Gunnar Fredriksson, Det politiska språket, six editions 1962-1974.

Ernesto Che Guevara, Gerillakrig, 1968.

Hilding Hagberg, Röd bok om svart tid, 1966.

Viveka Heyman, Jesajas bok, 1977.

Ragnar von Holten, Jolifanto Bambla, 1976.

Alfred Jarry, Kung Ubu (Ubu Roi), 1963.

Jorden och döden, Italian poetry. Selected and translated by Estrid Tenggren, 1961.

Ernst Jünger, Psykonauterna, and other titles.

Ernst Jünger, Psykonauterna, and other titles.Harry Järv, Die Kafka-Litteratur, Eine bibliographie, 1961.

Kim Il Sung, För en fredlig och självständig återförening av Korea, 1974.

Konsten att väcka förargelse. An anthology compiled by Ingemar Hedenius ,1964.

Kvinnan och revolutionen, texter om 200 års kamp för kvinnlig frigörelse. An anthology compiled by Folke Schimanski, 1972.

Claude Lévi-Strauss/Edmund/Guy Dumur, Claude Levi-Strauss och strukturalismen, 1969.

Georg Lukács, Historia och klassmedvetande, 1971.

Rosa Luxemburg, Jag var, jag är, jag blir, 1966.

Man Ray, Självporträtt, 1976.

Karl Marx, Kapitalet, first, second and third volumes 1971, 1973, 1974.

Ulrike Meinhof, Ulrike Meinhofs förbjudna tänkesätt, 1976.

Thomas Millroth, Maktens pyramider, 1976.

Friedrich Nietzsche, Sålunda talade Zarathustra/Sju ensamheter, 1970.

George Orwell, Essäer, selected and introduced by Olof Lagercrantz, 1970.

Pier Paolo Pasolini, Vittnet, 1978.

Patafysisk antologi, edited by Claes Hylinger, 1973.

15 titles by Ezra Pound from 1959 to 1982.

Leon Rappaport, Determinantan, 1978.

Bertrand Russel, Strid för freden, 1967.

Sigmund Freud - Psykoanalysens skapare, Liv och personlighet. Eyewitness stories, 1977.

C.P.Snow, De två kulturerna, translated by C.A. and Lillemor Wachtmeister, 1961.

Torsten Weimarck, Om konst, 1975.

Jan Östergren, Intervaller & Repriser, 1974.

William Carlos Williams, Gary Snyder, Henry James, William Burroughs, Eric Hermelin...

The distribution system used by the publisher changed over the years. Originally, Cavefors had used the old commission system, which meant that every bookshop in the country received one copy of every new book, which they then either accounted for at the end of the year or returned unsold. When this system ceased, Cavefors invented his own system. He gave a free copy to all booksellers who paid the full ”publisher’s price” (excluding sales tax and delivery costs) for one copy. That way, he got two copies out instead of one. He had agreements with about 150 booksellers country-wide. His books proved to be sought-after, and sold. Eventually he created another system for marketing and selling, not unlike those used by IKEA and mail-order companies. He presented his latest publications in regularly printed catalogues. At one point, more than 40,000 catalogues were being sent out to the members of the book club.

A more unusual form of publishing, not controversial but rather experimental, is Cavefors’s publication of artists’ books, in which the page is described ”as an alternative space”, ie used by the artist as a medium. These types of editions are not like those books of art which have to do mainly with the craft of making books. Artists’ books may sometimes look like normal books, but they are essentially idea-based art.

Here, Cavefors was a pioneer in Swedish publishing. As early as 1965 he published ”I PÅSEN” (”In the bag”), an artwork in a carrier bag and an example of Berndt Pettersson’s word and language art, published in connection with his exhibition at Galleri Karlsson in Stockholm, in 1965.

Other artists’ books would follow. They included Sture Johannesson’s ”S. K. O. en vetenskaplig dokumentation med fotnötter”, 1975 (”S.H.O.E. a scientific documentation with footnotes”). It contained full-page pictures of famous artists’ shoes.

Mats B’s Vet snut hut, vett snutt hutt, 1975.

Vita djuret by Peter Ortman and Ola Billgren, 1977.

Rolf Börjlind’s Persona Non Grata, 1977.

Carsten Regild’s Lupus Ultra, 1980. It was set to be published, but Lennart Eliasson intervened, so it was published by Regild’s own firm, Vargen, Stockholm 1980.

The graphic design of Cavefors’s books differed from that of other publishers. During the early years, this difference was of both format and cover. None of the books he himself designed say so. ”I didn’t want to parade my name in every book. It seemed exaggerated, as my name was used in the publisher’s name”, he said in response to my question about why he hadn’t included himself.

All other designers were credited.

The design aspect of his books was observed by Svensk Bokkonst, an institution that each year selects the 25 most beautiful Swedish publications, as early as 1961. That year, Cavefors received honourable mention for the firm’s publishing as a whole. The jury’s decision was even commented on in the catalogue: ”Equally pleasing is the jury’s decision to emphasise, in the foreword, the qualities of those books submitted by Cavefors publishing”.

Cavefors also got involved in the publishing of Verdandi-Debatt, after he had been approached by Carl-Adam Wachtmeister. Publications in the series included Lars Furhoff’s ”Kommunal skendemokrati” (”Municipal sham democracy”) and Lars Lönnroth’s ”Litteraturforskningens dilemma” (”The dilemma of literature studies”). In order to achieve larger editions, a partnership was initiated with Bokförlaget Prisma in Stockholm. Cavefors realised after a while that the published material was echoing the concerns of liberal social democrats too much, and Prisma carried on alone for a while before the project was abandoned.

Instead, Cavefors started the BOC series with polemical books such as ”Det politiska språket” (”Political language”) by Gunnar Fredriksson, and first editions of philosophical works, including Nietzsche’s ”Sålunda talade Zarathustra” and works by Roland Barthes and Michel Foucault, among others. Works of fiction in this series included books by Stig Claesson and Peter Weiss, and there were political works such as Stalin’s ”Teori och Praktik”.

The Zenith series was a paperback series whose editorial committee was made up of Lund leftists who had actually come from Zenit, a syndicalist periodical. Publications were exclusively in the field of political theory, with authors such as Göran Therborn, Torsten Bergmark and Andre Gunder Frank. In all, 22 volumes were published.

After a long hiatus, Cavefors contributed to the resuscitation of VOX, a literary magazine. This was at the suggestion of Sune Nordgren, and a few volumes were published with him as editor. VOX was the old first-publication magazine that Gleerups started in 1947. Poets Göran Printz-Påhlson, Ingemar Gustafson [Leckius] and Majken Johansson, among many others, published their first work in it.

RADIX magazine appeared in 1978, edited by Harry Järv. From 1980, it was published in Zürich and as of no.1, 1982, Cavefors himself assumed the editorial role.

Since Bo Cavefors Bokförlag went into liquidation, Cavefors has continued to publish books. This has been through his Verlag Bo Cavefors in Zürich, which he established back in 1977, before the solar eclipse in Lund. Here he published German editions of Wijkmark’s ”Die Jäger von Karinhall” and Wole Soyinka’s ”Der Mann ist Tot”, among others, as well as the RAF books, which probably caused some irritation among his persecutors in Sweden.

The basic idea behind the Zürich firm was to make use of the rights to editions in other languages, such as German, French and Italian. It was a good idea which never came to be realised. The Zürich firm did publish Ezra Pound’s ”Gajd till Kulchur”, with two titles actually, the Swedish one being ”Gajd till kultuuren” due to the rather intricate original title. The Zürich books were both in Swedish and German, in other words. Pound’s ”Homage to Sextus Propertius” was published by Bo Cavefors Verlag in Merano in 1982. The Zürich firm also published original editions of Jesuit writing, including works by Karl Rahner SJ and notably by Carlo Maria Martini SJ, Cardinal and Archbishop of Milan, whose publications were a great success.

The publishing firm of Näktergalen (Nightingale), in Verona, published four new volumes of Johannes Bobrowski, Roland Barthes, George Darien and Eric Hermelin.

In his vast and varied publishing achievement, Bo Cavefors’s passion for books, reading and writing is best expressed by the small, very carefully chosen and beautiful publications in his ”waistcoat-pocket books” series. These are personal, sometimes deeply private, but above all very honest, straightforward and surprising books. Some examples of the more than 200 titles to emerge from his workshop: ”En Kartusians dikter” (”Poems of a Carthusian”), ”Kartusiansk mystik” (”Carthusian Mysticism”), Ignatian texts, his own translations of poetry and his own texts such as the autobiographical ones, not included in the already mentioned books from 1995 and 1996. (Recordings of his own readings of the two aforementioned [Barnsliga memoarer and Valpen som ung man] books will be available for listening during the exhibition.)

I have become particularly attached to certain editions. These are the ones in which he reveals what are for me poignant fates and unknown contexts. It might be about Wilhelm Waiblinger, the genius, or about T.E. Lawrence (Lawrence of Arabia), or about Pier Paolo Pasolini, which was the last edition, in four volumes. They wore blood-red covers, and under the black band a letter had been inserted in which he writes, ”…but the attached work is, most likely, the last edition from Waistcoat-pocket Books, for the simple reason that the venture doesn’t amuse me any more.” Bo Cavefors.

One thing is very clear: Bo Cavefors is a brave publisher and human being, and not one of those who was blinded when the eclipse plunged Lund into darkness.

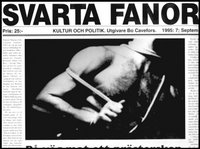

The best example of this is the fact that he continues to publish his own magazine, Svarta

Fanor [Black Standards]. The first issue was published in May 1994, and most people choked on it! The printed edition ceased with the triple issue no.16-17-18, 1995. It is now published as an e-mail newsletter with almost 600 subscribers – most of them voluntary!!

Fanor [Black Standards]. The first issue was published in May 1994, and most people choked on it! The printed edition ceased with the triple issue no.16-17-18, 1995. It is now published as an e-mail newsletter with almost 600 subscribers – most of them voluntary!!

Artists Leif Elggren and Kent Tankred are the creators of this important exhibition in Vita Kuben at Norrlandsoperan in Umeå. It opens on November 9 2002 and will close after December 4. The exhibition is available to the public during Norrlandsoperan’s opening hours.

(Translation by Tomas Tranæus)

Copyright©Leif Eriksson 2004, 2006

No comments:

Post a Comment